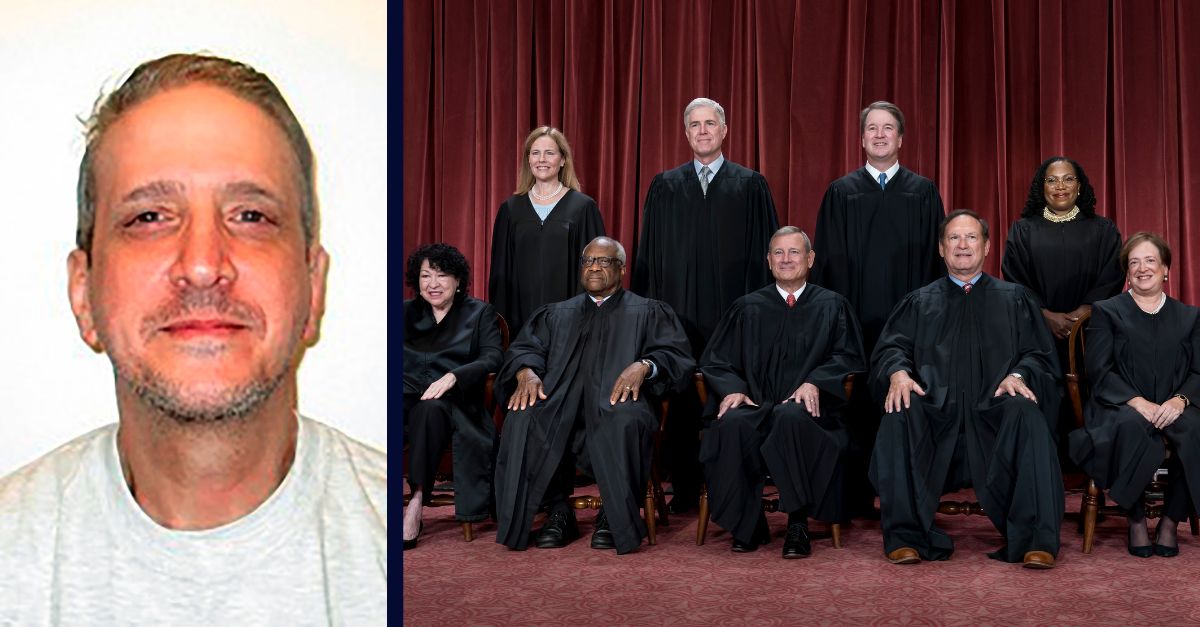

Left: Oklahoma death row inmate Richard Glossip (Oklahoma Department of Corrections via AP). Right: The justices of the U.S. Supreme Court (Alex Wong/Getty images).

In a highly unusual turn of events, the State of Oklahoma and the Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office have admitted they got a death penalty case wrong and are now imploring the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn a man’s decades-old conviction and grant him a new trial.

In the case stylized as Glossip v. Oklahoma, the respondents have now sided with the petitioner against the Sooner State’s own court system.

“Both the State of Oklahoma and the current Attorney General have resisted earlier efforts by Richard Glossip to attack his first-degree murder conviction and capital sentence,” the state’s brief begins.

That resistance faded last year when the state itself discovered evidence one of the prosecutors had “long suppressed” the fact their “one indispensable witness against Glossip lied on the stand” and how those same prosecutors “knowingly elicited his false testimony and then failed to correct the record,” according to the brief filed on Tuesday by Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond.

Explaining the atypical table-turning, Drummond is now going to battle with his state’s top criminal court.

“It is undisputed that the State not only withheld evidence of its star witness’s mental illness and perjury, but knowingly elicited false testimony providing an innocuous explanation for the disclosed facts,” the brief continues.

Glossip’s case has long been mired in controversy.

The 60-year-old inmate was first convicted in 1998 and then sentenced to die over the 1997 murder-for-hire of Barry Van Treese, who owned the Oklahoma City Best Budget Inn where Glossip worked as a manager. Everyone, however, agrees Glossip did not physically kill Van Treese. The murder itself was committed by Justin Sneed, who also worked at the motel at the time as an informal maintenance man.

After Van Treese was bludgeoned to death with a baseball bat, investigators focused their attention on Glossip and Sneed.

The former man was the first to be interviewed and eventually admitted to helping Sneed cover up the murder; Glossip was then charged as an accessory after-the-fact to murder. The latter man “evaded police for a week,” according to Drummond’s brief. When Sneed was finally captured, he “at first denied even recalling Glossip’s last name,” but eventually changed his story under police pressure and “professed that Glossip was the mastermind of the murder.”

Both men were then charged with murder in the first degree.

In 2001, Glossip’s original conviction was overturned due to ineffective assistance of counsel. The reviewing Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals (OCCA) remarked at length on defense counsel’s failure to confront the state’s “star witness” Sneed over the “numerous inconsistencies” between his police interviews and in-court testimony — among various other problems.

In 2004, Glossip was re-tried, re-convicted and re-sentenced to death — this time with the prosecution led by Oklahoma County assistant district attorney Connie Smothermon.

“Before retrial, given the centrality of Sneed’s testimony to the prosecution and the flaws in Glossip’s prior counsel’s examination of him, Glossip requested disclosure of ‘any and all statements made by Justin Blayne Sneed,'” the attorney general’s brief explains. “The State was required to provide those statements under Oklahoma law.”

Those statements were not provided to the defense.

During Glossip’s second trial, Smothermon questioned Sneed about whether he was on any prescription medication.

Sneed replied as follows: “When I was arrested I asked for some Sudafed because I had a cold, but then shortly after that somehow they ended up giving me Lithium for some reason, I don’t know why. I never seen no psychiatrist or anything.”

“So you don’t know why they gave you that?” Smothermon asked one time before allowing the thread to go un-pulled going forward.

Oklahoma’s top law enforcement official believes this exchange shows the prosecutor knowingly suborned perjury from Sneed.

As it turns out, Sneed had told Smothermon he was “on lithium” and he knew why — because he was being treated for bipolar disorder. And, as it also turns out, Sneed’s medical records — which were also repeatedly withheld from the defense — confirm the diagnosis.

The truth of what Sneed knew about his mental state, and what the prosecutor allowed him to testify about under oath, was only belatedly revealed after a series of post-conviction appeals. And, even then, only by the state itself — after Glossip had a close brush with death. In 2015, he was scheduled to be executed but prison officials realized hours ahead of his execution they were about to use the wrong drug.

After that, the controversy became political. A bipartisan group of 35 legislators secured an independent review by a law firm pro bono. That review led to the hiring of a Republican independent counsel.

During Glossip’s own appeals, the state gave him seven boxes of discovery. Those weren’t enough. During the state’s own investigation, an eighth box was uncovered which revealed the truth, Drummond says, in “[b]uried” handwritten notes by Smothermon which documented the mental health issues and the lithium regimen.

The attorney general is withering in his estimation of the prosecutor’s antics regarding Sneed’s diagnosis, treatment, and testimony.

From the brief, at length:

Smothermon disclosed neither her handwritten notes nor their substantive content — that Sneed was not in fact mis-prescribed lithium, but rather diagnosed with bipolar disorder and treated with lithium under the care of a psychiatrist — to the defense. And despite her knowledge of these facts, Smothermon elicited false testimony from Sneed on the subject.

…

Despite having taken handwritten notes confirming her knowledge of Sneed’s diagnosis and treatment and despite Sneed’s previous lies on the subject in a competency evaluation, Smothermon asked Sneed on the stand whether he was taking any medication. When Sneed falsely responded that he was mistakenly dispensed lithium and had never seen a psychiatrist, Smothermon did not correct the record, but doubled down to obtain a reaffirmation before moving on.

The perjury elicited by the state, Drummond argues, was no minor issue at trial. Rather, Sneed’s testimony, “was the key to transforming Glossip from after-the-fact accessory to criminal mastermind and motivating force behind a murder-for-hire agreement.”

“The centrality of Sneed’s testimony to the murder charged cannot be overstated,” Drummond goes on. “As reviewing courts have repeatedly acknowledged, the prosecution would not have been viable without Sneed’s testimony.”

In exchange for pinning the genesis of the alleged murder-for-hire on Glossip, Sneed struck a plea deal that avoided the death penalty.

Now, the two parties in the case — the state and the convicted — both agree with one another. But only after a lengthy process.

In 2022, the OCCA, acting on the prior attorney general’s wishes, set an execution date. Glossip appealed again and the date was stayed by the governor to allow the court time to consider the appeal. Meanwhile, Box 8 was discovered in January 2023, the second state-initiated case review concluded in April 2023, and everyone was, finally, on the same side. That, is, except for the OCCA.

Despite the state’s “confessed constitutional errors” of various varieties — including discovery violations under the Brady doctrine and broader Due Process concerns — the appellate court denied the shared request for a retrial. The OCCA reasoned that Glossip either made his challenge too late or mused that he never challenged Sneed’s credibility on the lithium issue because his defense counsel did not “want to inquire about Sneed’s mental health” for fear of “showing that he was mentally vulnerable to Glossip’s manipulation.”

Both excuses are rubbished by Drummond, who refers to the lower court’s analysis as “gold-medal doctrinal gymnastics.”

First, the attorney general argues, the defense had no way of knowing Sneed lied about his lithium prescription until last year when Smothermon’s handwritten notes proved the state relied on perjury to win the case. Second, the “prosecution’s felt need to inoculate Sneed’s disclosed lithium use by eliciting a false narrative” further frustrated the defense because Glossip was prevented “from identifying the lie as a lie and exploiting it through a devastating cross-examination.”

Drummond again rails against the appeals court for seemingly vindicating those two instances of “prosecutorial misconduct.”

“Both involved a key fact about the key witness,” the brief continues. “And the one-two punch of concealment and eliciting a false cover story deprived the defense of critical opportunities for impeachment and developing an alternative explanation for the brutal nature of the murder. The OCCA’s decision to whitewash those serious and reinforcing constitutional violations cannot be the final word.”

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]

.jpeg) 1 week ago

18

1 week ago

18

English (US)

English (US)