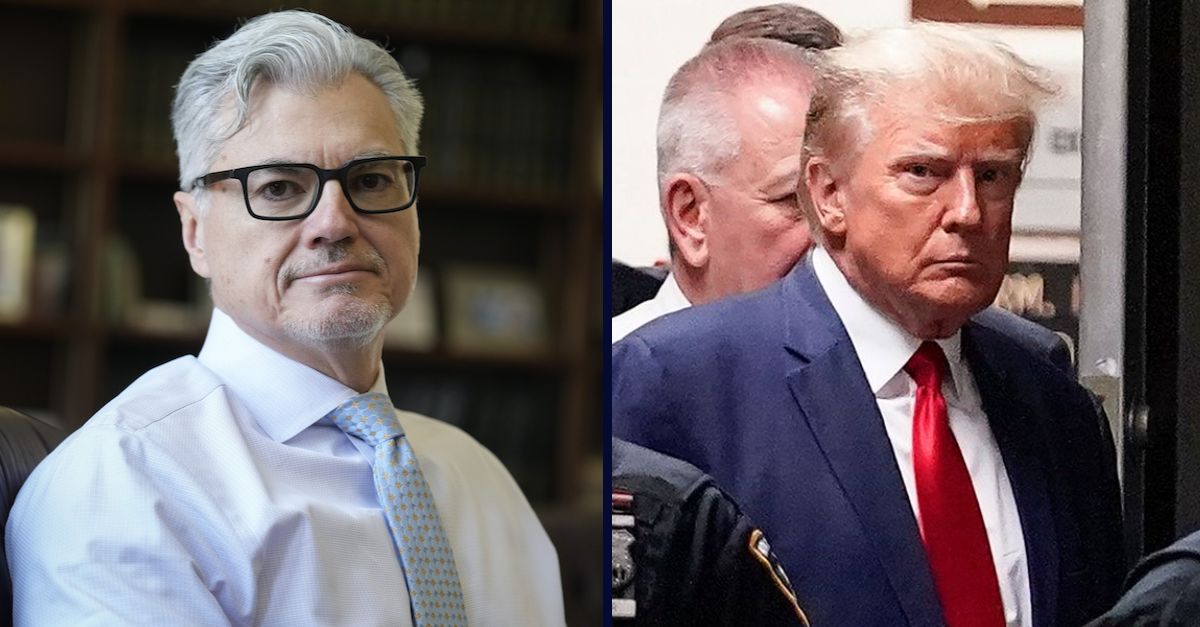

Left: Judge Juan Merchan poses for a picture in his chambers in New York, Thursday, March 14, 2024. Merchan is presiding over Donald Trump’s hush money case in New York (AP Photo/Seth Wenig). Right: FILE – Former President Donald Trump is escorted to a courtroom, April 4, 2023, in New York (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer, File).

Under New York law, a criminal defendant has a right to know before trial what prior crimes or acts the prosecution intends to cross examine the defendant about if he or she elects to testify. The trial court will then hold what is called a Sandoval hearing, named after a 1974 case, called People v. Sandoval, in which the New York Court of Appeals — the highest court in the state — outlined when and how such evidence is admissible. Pursuant to Sandoval, New York Supreme Court Justice Juan Merchan ruled this week on what evidence the prosecutors can use to cross examine former President Donald Trump if he chooses to testify.

Although Merchan’s ruling provides guidance to the prosecution and defense on what evidence will be fair game to impeach the former president, it’s difficult to square with the spirit of Sandoval and has the potential to have a chilling effect on Trump and impermissibly dissuade him from testifying.

Merchan ruled that prosecutors can use the following evidence to cross examine Trump if he chooses to testify:

- New York civil fraud verdict: Merchan ruled that Trump may be cross-examined on the verdict in the New York civil fraud case brought by state Attorney General Letitia James that found he violated the law by fraudulently inflating the value of his properties. Prosecutors may also ask Trump about the two violations of New York Supreme Court Justice Arthur Engoron’s gag order during that trial last fall.

- E. Jean Carroll defamation verdicts: Prosecutors will be allowed to cross-examine Trump about both E. Jean Carroll verdicts in federal court where juries found Trump defamed Carroll, a veteran writer who said Trump assaulted her in a New York department store in the 1990s.

- Settlement with New York attorney general: Prosecutors will be allowed to cross-examine Trump about the settlement he reached with the New York attorney general that led to the dissolution of the Donald J. Trump Foundation.

Merchan’s ruling thus gives the prosecution a wide berth in its introduction of potential impeachment evidence — used to discredit the witness and to persuade the jury that the witness is not being truthful — thereby discouraging Trump from taking the stand in his own defense.

But the opportunity to testify is a necessary corollary to the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee against compelled testimony. As the U.S. Supreme Court put it in the case of Harris v. New York: “Every criminal defendant is privileged to testify in his own defense, or to refuse to do so.” Merchan has given permission for the prosecution to cross-examine Trump regarding civil cases that are far removed from the hush-money case, as well as from the contempt finding from the recent civil case tried in New York. There is no valid basis to permit evidence of these other civil cases, as the nature of the conduct or the circumstances in which it occurred do not bear much on the issue of Trump’s credibility. Moreover, Merchan’s decision sends a chilling message to Trump on his right to testify in his own defense.

Merchan’s ruling gives the appearance that he is trying to prevent and intimidate Trump from testifying. For example, Merchan decided prosecutors from the office of Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg can question Trump about the recent civil case where the Attorney General obtained a $454 million verdict against Trump. This will open the door for the jury to think that because Trump lied on his financial statements to banks, then he must have lied about his business records. This is the very prejudice that Sandoval sought to prevent.

Merchan is also going to permit prosecutors to question Trump about two defamation verdicts in the E. Jean Carroll cases. A federal jury found that Trump defamed her and awarded her significant damages in each of her cases. The hush-money jury could conclude that another jury found that Trump told falsehoods and that should be a guide to them in his criminal case.

Furthermore, both of these civil cases are currently on appeal and may be reversed and remanded for new trials. Permitting cross-examination on them would thus require Trump to answer questions about potentially overturned findings of fact. Beyond that, civil cases have a burden of proof less than beyond a reasonable doubt, the burden of proof Bragg must overcome in Trump’s criminal trial.

How can Merchan explain all of this to the Trump hush-money jury in a way that does not confuse them, especially if the reversals were to occur after Trump is cross-examined? Perhaps more critically, if Trump does not testify in his criminal case and he is convicted, and then either of the civil cases are overturned, Trump may be able to argue that his conviction should be overturned because he was chilled from testifying in his own defense.

The recent decision of the New York Court of Appeals overturning the rape conviction of Harvey Weinstein illustrates the thin ice Merchan is ruling from. In that case, the trial court permitted the prosecution to introduce into evidence — and cross-examine Mr. Weinstein about — prior, uncharged alleged bad acts. The New York Court of Appeals held this had the effect of “diminish[ing] defendant’s character before the jury” and “undermin[ing] defendant’s right to testify,” and that the only “remedy for these egregious errors is a new trial.” Should Merchan not reconsider his ruling in the Trump matter, the prosecution runs the risk of having any conviction it earns overturned on appeal — which would be a disastrous result for Bragg.

Merchan has also permitted the Bragg team to question Trump, if he takes the stand, about his violation of the gag order in his recent civil fraud case presided over by Engoron. Trump spoke about Engoron’s law clerk in violation of the gag order and was fined for those comments. To be sure, this was bad conduct, but Sandoval stands for the principle that bad conduct cannot be used to show that Trump is a bad person, and therefore guilty.

The final area the Bragg team can question Trump about concerns financial irregularities over the dissolution of the Trump Foundation in 2018. Again, under Sandoval, such questioning should not be permitted. Explaining what the Trump Foundation case was all about — much less how there is any relevance to the crimes charged in the Bragg prosecution — will necessarily confuse the hush-money jury and provide little insight into the elements of the crimes charged.

Courts in New York, guided by Sandoval, permit the prosecution to question the defendant about prior criminal convictions in limited circumstances, but few extend that already narrow ground to findings of civil liability. Trump has no prior criminal convictions, but if he chooses to take the stand, he will be forced to open himself up to questioning about other civil matters. Consequently, his legal team will be justifiably concerned that the jury will think he is a bad person and therefore guilty of these charges.

Merchan’s decision to let this other evidence in if Trump testifies will have a chilling effect on his decision to testify. It is in our country’s best interest that Trump testifies. Trump should not be chilled from testifying and, if he testifies, the jury can decide if he is telling the truth in his criminal case — and the rest of us can make that same determination for ourselves.

John P. Fishwick Jr. is the founder and owner of Fishwick & Associates PLC, a trial law firm in Roanoke, Virginia. John previously served as the United States Attorney for the Western District of Virginia.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]

.jpeg) 2 weeks ago

23

2 weeks ago

23

English (US)

English (US)