Richard Nixon speaks during White House news briefing in Washington. (AP Photo/Henry Burroughs.), Special counsel Jack Smith (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File), Donald Trump (AP Photo/David Yeazell)

In a Supreme Court clash of epic proportions on an issue that threatens to undo the former president’s Jan. 6 prosecution and grant more power to future presidents, the Special Counsel’s Office and attorneys for Donald Trump appeared before the nine justices on the subject of immunity.

Near the start of oral arguments, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson took an interest in, perhaps, the most famous pardon in American history — Richard Nixon’s.

“What was up with the pardon of President Nixon?” Jackson asked Trump attorney John Sauer directly, strongly suggesting that her view of the case is in line with her 2019 district court opinion that “Presidents are not kings.”

Put simply, Jackson was asking Sauer why Nixon needed a pardon if presidents had the “absolute immunity” that Trump claims to have.

“If everybody thought that presidents couldn’t be prosecuted, then what was that about?” she asked.

“Well, he was under investigation for both private and public conduct at the time — official acts and private conduct — and I think everyone has under properly understood that the president, since, like, President Grant’s carriage-riding incident, everyone has understood that the president could be prosecuted for private conduct,” Sauer answered.

In a Jack Smith brief, the special counsel called former President Richard Nixon and Watergate the “closest historical analogue” to Trump and Jan. 6. Smith, anticipating that the justices might find a former president has “some immunity” from being prosecuted for official acts, argued that even if that is so the Jan. 6 case against Trump can still proceed given Trump’s “substantial private conduct in service of [his] private aim” of staying in power.

The special counsel argued that Nixon’s resignation and subsequent pardon by President Gerald Ford was “implied” proof that the 37th president of the United States had criminal exposure from acts committed while in office once he was out of office.

“The closest historical analogue is President Nixon’s official conduct in Watergate, and his acceptance of a pardon implied his and President Ford’s recognition that a former President was subject to prosecution,” Smith wrote. “Since Watergate, the Department of Justice has held the view that a former President may face criminal prosecution, and Independent and Special Counsels have operated from that same understanding. Until petitioner’s arguments in this case, so had former Presidents.”

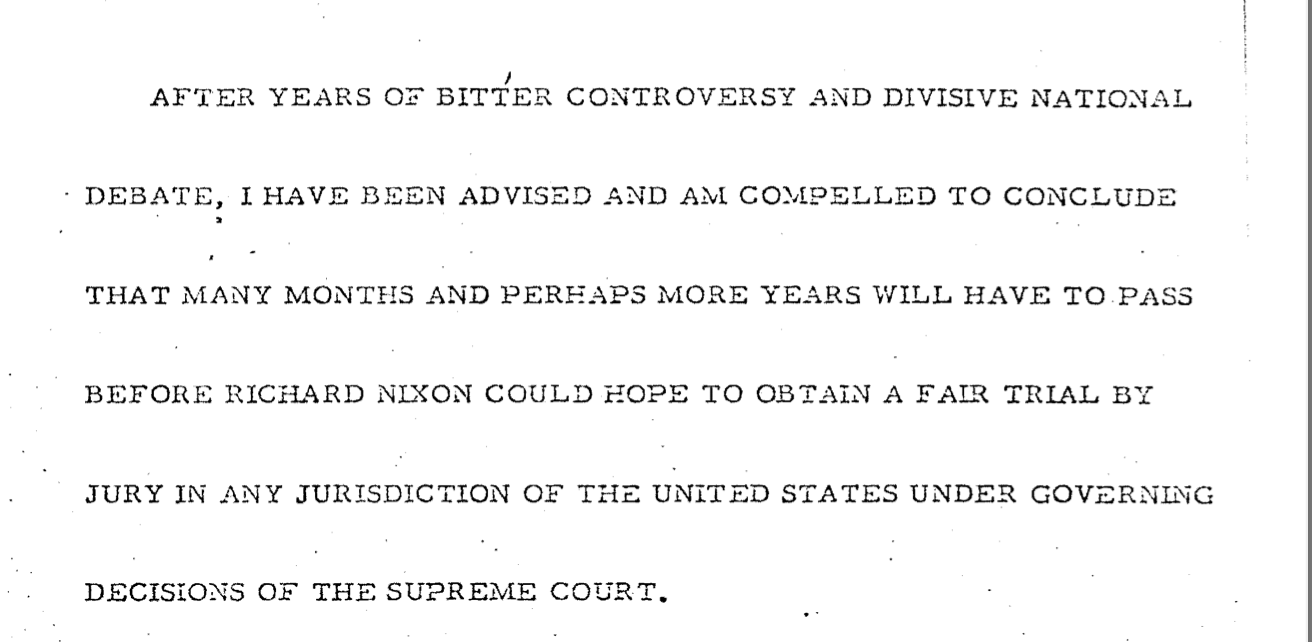

Smith linked to Ford’s statement on pardoning Nixon, in which Ford said that he did not think Nixon could get a fair criminal trial.

“After years of bitter controversy and divisive national debate, I have been advised and am compelled to conclude that many months and perhaps more years will have to pass before Richard Nixon could hope to obtain a fair trial by jury in any jurisdiction of the United States under governing decision of the Supreme Court,” Ford said.

Notably, Trump lawyers argued that Nixon’s pardon actually helped their argument.

“President Ford pardoned President Nixon, but President Nixon faced charges for private conduct, not just official acts,” the Trump team asserted, pointing to Ford’s doubts that Nixon could have gotten a fair trial.

“Moreover, President Ford correctly determined that the prosecution of a former President would be incurably divisive and destructive,” the brief said. “Citing the ‘years of bitter controversy and divisive national debate,’ President Ford stated that ‘years will have to pass’ before Richard Nixon could hope to obtain a fair trial by jury in any jurisdiction of the United States; that in such a trial, ‘ugly passions would again be aroused, our people would again be polarized in their opinions, and the credibility of our free institutions of government would again be challenged,’ and that prosecuting the former President would ‘prolong the bad dreams that continue to reopen a chapter that is closed.’ Thus, Ford made the same judgment as the Framers — that the prosecution of a former President should not, and could not fairly, proceed in Article III courts.”

In late February, the high court agreed to hear oral arguments on “whether and if so to what extent does a former president enjoy presidential immunity from criminal prosecution for conduct alleged to involve official acts during his tenure in office?”

In December, the special counsel urged the high court to grant a rare writ of certiorari before judgment, asking the justices to act before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled on Trump’s “absolute immunity” arguments — and to treat the case like Watergate.

Days later, Trump’s attorneys urged the justices to proceed in a “cautious, deliberative manner — not at breakneck speed,” contrary to Smith’s proposal. A short time later, the Supreme Court declined to sign off on Smith’s ask in a one-line denial.

In early February, the D.C. Circuit ruled against Trump, writing: “For the purpose of this criminal case, former President Trump has become citizen Trump, with all the defenses of of any other criminal defendant. But any executive immunity that may have protected him while he served as president no longer protects him against this prosecution.” Then, at the end of February, the justices took up the immunity question and set the oral argument we now discuss.

Between then and now, a slew of briefs were filed for and against Trump’s immunity theories, including the Nixon-focused filings.

Colin Kalmbacher contributed to this report.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]

.jpeg) 3 weeks ago

19

3 weeks ago

19

English (US)

English (US)